Can You Be A Jew And Not Understand Judaism? Yes.

Either Elite Jews Are NOT Jews or The Masses That Know Not of Their Evil "Elite" Practices Are Not Jews

Either Elite Jews Are NOT Jews or The Masses That Know Not of Their Evil Practices Are Not Jews

Leslie Wexner’s Inner Demon

This short excerpt from Whitney Webb’s upcoming book “One Nation Under Blackmail” examines an obscure media profile of Leslie Wexner, Jeffrey Epstein’s mentor, from the 1980s that contains disconcerting revelations about Wexner’s personality and his inner world.

BY WHITNEY WEBB

JUNE 10, 2022

5 MINUTE READ

1985 was the year that Leslie Wexner became a billionaire. It was also that year that the chairman of The Limited (now L Brands) began to build up his public persona. This effort to “re-brand” himself began with a series of fawning media profiles. The main outlets that participated in Wexner’s first main, personal PR campaign were written by prominent New York City-based outlets, like New York Magazine and the New York Times.

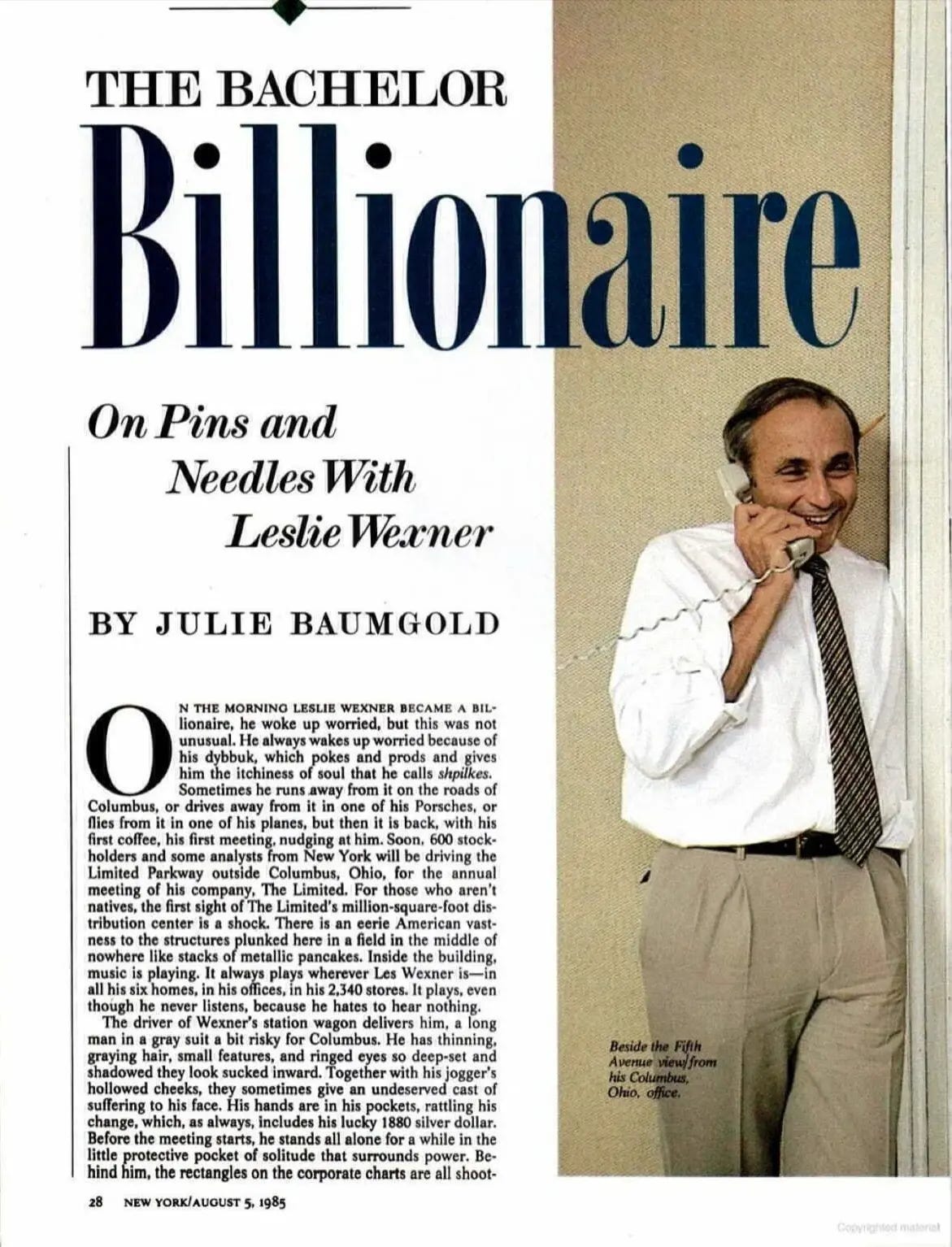

The New York magazine profile, which was the cover story for its August 5, 1985 issue, was entitled “The Bachelor Billionaire: On Pins and Needles with Leslie Wexner.” Though filled with photos of a middle-aged Wexner grinning and embracing friends as well as lavish praise for his business dealings and his “tender” and “gentle” personality, one of the main themes of the article revolves around what is apparently a spiritual affliction or mental illness of Wexner’s, depending on the reader’s own spiritual persuasion.

The New York Magazine article opens as follows:

“On the morning Leslie Wexner became a billionaire, he woke up worried, but this was not unusual. He always wakes up worried because of his dybbuk, which pokes and prods and gives him the itchiness of the soul that he calls shpilkes [“pins” in Yiddish]. Sometimes he runs away from it on the roads of Columbus, or drives away from it in one of his Porsches, or flies from it in one of his planes, but then it is back, with his first coffee, his first meeting, nudging at him.”

One may interpret this use of shpilkes, literally “pins” or “spikes” in Yiddish and often used to describe nervous energy, impatience or anxiety, as Wexner merely personifying his anxiety. However, his decision to use the word dybbuk, which he does throughout the article, is quite significant. Also notable is how Wexner goes on to describe this apparent entity throughout the article and his intimate relationship with it.

First page of New York Magazine’s 1985 profile of Wexner

As defined by Encyclopedia Britannica, a dybbuk is a Jewish folklore term for “a disembodied human spirit that, because of former sins, wanders restlessly until it finds a haven in the body of a living person.” Unlike spirits that have yet to move on but possess positive qualities, such as the maggid or ibbur, the dybbuk is almost always considered to be malicious, which leads it to be translated in English as “demon”. This was also the case in this New York magazine profile on Wexner.

The author of that article, Julie Baumgold, describes Leslie Wexner’s dybbuk as “the demon that always wakes up in the morning with Wexner and tweaks and pulls at him.” Wexner could have easily chosen to frame the entity as a righteous spirit (maggid) or as his righteous ancestors (ibbur) guiding his life and business decisions, especially for the purpose of an interview that would be read widely throughout the country. Instead, Wexner chose this particular term, which says a lot for a man who has since used his billions to shape both mainstream Jewish identity and leadership in both the US and Israel for decades.

As the article continues, it states that Wexner has been with the dybbuk since he was a boy and that his father had recognized it and referred to it as the “churning”. Per Wexner, the dybbuk causes him to feel “molten” and constantly pricked by “spiritual pins and needles”. It apparently left him at some point as a young man, only to return in 1977 when he was 40, half-frozen during an ill-fated trip up a mountain near his vacation home in Vail, Colorado. This specific trip is when Wexner says he both rejoined with his childhood dybbuk and decided to “change his life.”

He told New York magazine that his dybbuk makes him “wander from house to house”, “wanting more and more” and “swallowing companies larger than his own.” In other words, it compels him to accumulate more money and more power with no end in sight. Wexner later describes the dybbuk as an integral “part of his genius.”

Wexner further describes his dybbuk as keeping “him out of balance, emotionally stunted, a part of him — the precious, treasured boy-son part — lagging behind [the dybbuk].” This is consistent with other definitions of the term in Jewish media, including a feature piece published in the Jewish Chronicle. That article first defines the term as “a demon [that] clings to [a person’s] soul” and then states that: “The Hebrew verb from which the word dybbuk is derived is also used to describe the cleaving of a pious soul to God. The two states are mirror images of each other.” Per Wexner’s word choice and his characterization of what he perceives as an entity dwelling within him, the entity — the dybbuk — is dominant while his actual self and soul “lags behind” and is stunted, causing him to identify more with the entity than with himself.

This is also reflected in the concluding paragraph of the New York magazine article:

“Les Wexner picks up his heavy black case and flies off in his Challenger, with his dybbuk sitting next to him, taunting and poking him with impatience, that little demon he really loves. The dybbuk turns his face. What does he look like? ‘Me,’ says Leslie Wexner.”

Outside of the spiritual aspect of this discussion, it can also be surmised from the above that there is a strong possibility that Wexner suffers from some sort of mental disorder that causes him to exhibit two distinct personalities which continuously battle within him. What is astounding is that he describes this apparent affliction to a prominent media outlet with pride and the author of the piece weaves Wexner’s “demon” throughout a piece that seeks to praise his business acumen above all else.

Yet, perhaps the most troubling aspect of Wexner’s experience with his “dybbuk”, whether real or imagined, is the fact that Wexner, in the years before and after this article was published, has had a massive impact on Jewish communities in the US and beyond through his “philanthropy.” Some of those philanthropic efforts, like the Wexner Foundation, saw Wexner mold generations of Jewish leaders through Wexner Foundation programs while others, such as the Mega Group, see the organized crime-linked Leslie Wexner joined by several other like-minded billionaires, many of which also boast considerable organized crime connections, in an effort to shape the relationship of the American Jewish community, as well as the US government, with the state of Israel.

For a man of such influence in the Jewish community, why has there been essentially no questions raised as to Wexner’s role in directing the affairs of that ethno-religious community given that he has openly claimed to be guided by a “dybbuk”? This is particularly odd when one considers that Wexner has come under increased scrutiny in recent years after his protege and closest associate for decades, Jeffrey E. Epstein, was outed as both a pedophile and serial sex trafficker. Did Wexner’s dybbuk draw him to Epstein and prompt him to financially support his horrific crimes against minors?

Note: The above is an adapted excerpt from Whitney Webb’s upcoming book “One Nation Under Blackmail: the sordid union between Intelligence and Organized Crime that gave rise to Jeffrey Epstein”. Those interested may pre-order the book directly from the publisher’s website or from Amazon.